While most people, children and adults, have seen the three Shrek films, very few have read the marvelous picture book, which William Steig published with an exclamation mark—Shrek!—in 1990. In keeping with the postmodern spirit of the last twenty-five years, Steig modestly produced one of the best examples of how the fairy tale has been fractured and continually transformed, indicating its radical potential in our digital age, especially with the production and success of the twenty-first century digitally animated films. Since very few reviewers of the film have paid attention to the book Shrek!—not to mention book reviewers—I would like to summarize the plot briefly and comment on the great wry morality and humanity of the tale.

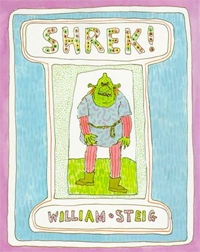

Steig’s Shrek! is very different in tone and style from the film. The title is based on a Yiddish expression that means “horror” or “terror,” not “fear” as some reviewers have said. Schrecken in German and Yiddish means to scare, terrify, or horrify, and the ogre Shrek on the cover of Steig’s book is a scary figure. He has a green face with protruding ears and a bald head with a pointed top. His face is spotted with black stubbles; his eyes are red; his nose large and round; and his teeth, sharp and crooked. He is tall and barrel chested. His fingernails on his green hands are long. He wears a multi-colored violet tunic with a belt around his midriff and striped pants. The color combinations change at times throughout the book, but not his features and character:

His mother was ugly and his father was ugly, but Shrek was uglier than the two of them put together. By the time he toddled, Shrek could spit a flame of full ninety-nine yards and vent smoke from either ear. With just a look he cowed the reptiles in the swamp. Any snake dumb enough to bite him instantly got convulsions and died.

One day Shrek’s parents kick him out of the swamp and send him into the world to do damage. So the entire question of evilWhat is evil? Who causes evil?is relativized from the very beginning. The anti-hero retains power and questions what heroism is about. Along the way he encounters a witch, who tells his fortune: he will be taken to a knight by a donkey, and after conquering the knight, he will marry a princess who is even uglier than he is. Wherever he goes, every living creature flees because he is so repulsive. When he comes upon a dragon, he knocks it unconscious. Then he has a dream in which children hug and kiss him, and such a paradisaical vision—not unlike a scene in Oscar Wilde’s “The Unhappy Giant”—is a nightmare for him.

He wakes to meet the donkey that takes him to the nutty knight who guards the entrance to the crazy castle where the repulsive princess waits. After he defeats the knight, he has the real test of his life: he enters a room filled with mirrors, and for the first time he learns what fear is when he sees how hideous he is. At the same time, this recognition raises his self-esteem, and he is “happier than ever to be exactly what he is.” Once he has passed this test, so to say, he has a “romantic” meeting with the ugly princess:

Said Shrek: “Your horny warts, your rosy wens,

Like slimy bogs and fusty fens,

Thrill me.”

Said the princess: “Your lumpy nose, your pointy head,

Your wicked eyes, so livid red,

Just kill me.”

Said Shrek: “Oh, ghastly you,

With lips of blue,

Your ruddy eyes

With carmine sties

Enchant me.

I could go on,

I know you know

The reason why

I love you so

You’re so ugh-ly! “

Said the princess: “Your nose is so hairy,

Oh, let is not tarry,

Your look is so scary,

I think we should marry.”

Indeed, they do marry, and they are married by the dragon, who looks more like an alligator in a green robe, and Steig comments: “And they lived horribly ever after, scaring the socks off all who fell afoul of them.”

This mock fairy tale plays with all the conventions of the traditional folk and fairy tale to provoke readers to consider the relative nature of evil and beauty. Instead of a handsome prince or a gifted third son, there is an outsider from the swamps, ugly and stinking, who wins a repulsive princess by overcoming fear of himself. The tale is obviously a parody of the Grimms’ “The Young Man Who Went Out in Search of Fear,” but is also more than that, for Steig levels the playing field for people considered to be despicable and evil. Shrek represents the outsider, the marginalized, the Other, who could be any of the oppressed minorities in America. He may even come from the streets of the Bronx, and the humor of the tale is clearly identifiable as New York Jewish humor. What was once a European folk tale has become, through Steig’s soft water color images and brazen irreverent language, a contemporary literary fairy tale that thrives on playfulness, topsy-turvy scenes, and skepticism. This is a fairy tale that radically explodes fairy tale expectations and fulfills them at the same time: the utopian hope for tolerance and difference is affirmed in an unlikely marriage sanctified by a dragon. The ogre and his wife will continue to frighten people, but they will be happy to do so in the name of relative morality that questions the bias of conventionality associated with evil.

Professor Jack Zipes, Director of the Center for German and European Studies at the University of Minnesota, teaches courses and conducts research about the critical theory of the Frankfurt School, folklore and fairy tales, romanticism, theater, and contemporary German literature with a focus on German-Jewish topics. In addition to his scholarly work on children’s literature, he is an active storyteller in public schools and has worked with various children’s theaters.